As the oft-repeated verse goes, “So, brothers and sisters, because of God’s mercies, I encourage you to present your bodies as a living sacrifice that is holy and pleasing to God. This is your appropriate priestly service” (Romans 12:1). So also the oft-repeated accompanying comment: Worship is holistic. Singing in church has little value if it something less than an expression of the individual and church’s wider commitment to God. When the whole life is directed towards him, even the mundaneness of taking a shower is taken into this position of worship. Nothing is excluded from this living sacrifice, except sin, that which is opposed to God and his plan of redemption. This is not to say that sin prevents it, however. As the Spirit worked in Jesus so the Spirit works in us. We can offer our lives as worship while we await for sin and death to be finally overcome.

What place does doubt play in this very short sketch of the Christian life? Is it sin that will be done away with when the world is brought into new creation? Or is it, somehow, an expression of the life directed towards God? A surface reading of the New Testament suggests the former:

But anyone who needs wisdom should ask God, whose very nature is to give to everyone without a second thought, without keeping score. Wisdom will certainly be given to those who ask. Whoever asks shouldn’t hesitate. They should ask in faith, without doubting. Whoever doubts is like the surf of the sea, tossed and turned by the wind. People like that should never imagine that they will receive anything from the Lord. They are double-minded, unstable in all their ways.

(James 1:5-8).

Doubt could be understood as hesitating to approach God and ask him for something or, having asked God, hesitating to believe that the prayer will be answered. For James, doubt in this sense would probably not be a form of worship! This makes sense when seen in the context of new creation: “Now we see a reflection in a mirror; then we will see face-to-face. Now I know partially, but then I will know completely in the same way that I have been completely known” (1 Corinthians 13:12). Why would the Spirit bring us to doubt if we will one day be free from all doubt?

However, the question becomes more complicated when understood in the context of the wider biblical picture. At the end of 12 chapters in Ecclesiastes surveying the absurdities and evils of life the Teacher can conclude, “Perfectly pointless… everything is pointless” (12:8). Add to that the second voice in the postscript. Not only, “Worship God and keep God’s commandments because this is what everyone must do” (v.13) but, surprisingly, “The Teacher searched for pleasing words, and he wrote truthful words honestly” (v.10). Apparently the Teacher who decried the absurdities and evils was not misguided! The narrator who opens and closes Ecclesiastes reassures us that Teacher’s doubts are not only compatible with the life of worship but actually worth reflecting on.

This is true also of the Psalms:

But now you’ve rejected and humiliated us.

You no longer accompany our armies.

You make us retreat from the enemy;

our adversaries plunder us.

You’ve handed us over like sheep for butchering;

you’ve scattered us among the nations.

You’ve sold your people for nothing,

not even bothering to set a decent price.(Psalm 44:9-12).

This is not the one-off, sinful musings of a person who has set their self against God. It is holy writ, taken up by the people of God and sanctified as the language of prayer and worship. Would you kiss your mother with that mouth, let alone your God?

An interesting case is Job, whom, as the story goes, God allows Satan to afflict by killing off his children and livestock, and striking him with sores all over his body. Job’s initial responses to the horror include praising God despite the situation — “The Lord has given; the Lord has taken; bless the Lord’s name” (1:21) — and even defending God — “Will we receive good from God but not also receive bad?” (2:10). However, in the main body of text we encounter a seemingly different Job: “Does it seem good to you that you oppress me, that you reject the work of your hands and cause the purpose of sinners to shine?” (10:3). God does not just seem distant but positively evil: “You know that I’m not guilty, yet no one delivers me from your power” (10:7). Which of these set of statements is spoken in faith or worship? It is hard to imagine any liturgical context where such language is directed in faith to God above, that is, whatever faith in that context would mean! It should also be remembered that, after much dialogue with the friends who apparently came to comfort him, Job is answered by God himself with the longest uninterrupted divine speech in the Bible. At the conclusion of this speech Job affirms again his faith in God’s power. He is declared righteous in contrast to his friends who “didn’t speak correctly, as my servant Job” (42:8).

In what sense can these examples be considered doubt? Maybe not in James’ sense. At least in the case of the Psalms and Job, such utterances are directed towards God rather than in a place apart from him. They arise from the mouths of those who have faith because, despite the content of their complaints, they do not direct it at a subject other than God. They are not uttered “behind his back,” so to speak. And it may be too simplistic to consider them as wavering. There is an urgency in the examples given which seeks answers from heaven. The supplicants are persistent in seeking God to respond to their situations. Thus by doubt I mean that which arises from either having seen God at work in history or more generally from an expectation that God’s being means that life should prevail over death and yet does not see this at work at present: Biblical doubt concerns the cries directed towards the One who could and should be present but is yet absent.

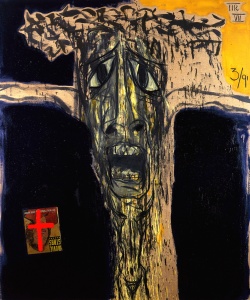

This brings us to a New Testament example. Matthew and Mark record Jesus’ last words on the cross as “My God, my God, why have you forsaken/abandoned me?” (Mark 15:33). By abandonment here I do not see some split in the Trinity (which is probably impossible and with which the world and God would cease to exist), but the simple continuation of the Old Testament tradition of the suffering righteous, as Psalm 22, the psalm Jesus quotes here, shows. Jesus has been abandoned by his Father insofar as his Father did not deliver him from those who crucified him. His abandonment is in the unanswered prayers offered in Gethsemane: “Abba, Father, for you all things are possible. Take this cup of suffering away from me. However—not what I want but what you want” (Mark 14:36). It is Jesus’ abandonment which brings this form of doubt into the Christian life of worship.

This also allows for doubt to be seen in the context of new creation. Both the passion narrative and Psalm 22 point to Jesus’ deliverance: “Don’t be alarmed! You are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised. He isn’t here” (Mark 16:6). God did not leave his servant to die but “he didn’t despise or detest the suffering of the one who suffered—he didn’t hide his face from me. No, he listened when I cried out to him for help” (Psalm 22:24). Doubt will be done away with. Yet, as long as creation remains the world of sin and death, doubt remains an important part of the Christian life. The end of Jesus and the psalmist’s story does not mean that there was never a middle. We are in the middle, the redemption of which will one day be brought to completion, and as such we cannot be detached from this middle but stand with it and share in its fears, worries, and doubts. In the same chapter we find the call to holistic worship we also find: “Be happy with those who are happy, and cry with those who are crying” (Romans 12:15). We need to creatively incorporate doubt and protest into our personal and communal worship.

I end with three of my own doubts that I direct towards the only One who could possibly one day answer them:

- How can I celebrate the victories and glimpses of redemption that you bring in my life and the lives of others when so many people are left seemingly untouched by grace and love?

- I can see how you can redeem Jesus’ suffering, who took the cross upon himself willingly and was rewarded with resurrection life. But how can you redeem those who suffer unwillingly?

- Through the work of the Spirit in the present it is possible to begin to imagine a world without sin and death. In this sense I can see the future of the world being redeemed. But how can this redemption touch every ugly and unspeakable corner of history? You can offer us a better future but how can you offer those who have suffered a better past?